A trip report from the Deasey Mountain hike on August 27, 2022

Continue readingThere and Back Again-Waterlilly’s hike of the Maine IAT

A Hike Report by Waterlilly

Continue readingBowlin to Lunksoos Trail Maintenance Work Trip

Three beautiful fall days clearing trail and resetting signpost on the Maine IAT.

Continue readingSisters on Six Day Winter Adventure

A Trek on IAT in Morocco

Larry Luxenberg shares his story of hiking the IAT in Morocco.

Continue reading‘Monumental’ – A Journey through Katahdin Woods and Waters

Barnard Mountain Hike 2017

Bark Camp Meadow

In Ed Werler’s Book, The Call of Katahdin, he mentions a location called Bark Camp Meadow on the East Branch of the Penobscot River.

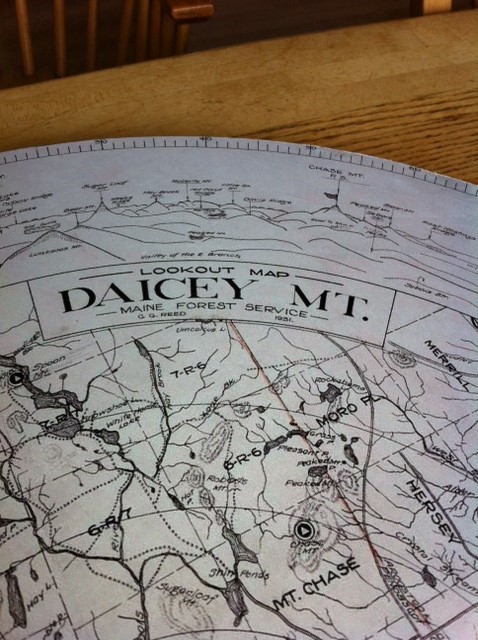

The year was 1947 and Ed, along with his wife Mary Jane and two dogs, had agreed to spend that fire season as Warden at the Daicey Mountain Fire Lookout. There was a warden’s cabin about halfway up the mountain where they would be living for several months and they needed to get their food and household gear “wangan”* up the East Branch of the Penobscot River from Grindstone, where the East Branch met the road, to the trail at the foot of the mountain leading to the warden’s and the fire cabins. This was a distance of about 16 miles upriver.

They met their riverman “Bink” and loaded their “wangan” and headed up river in a 20 foot Old Town canoe. They spent the first night at Whetstone cabin and the next day arrived at a place that Bink called Bark Camp Meadow. It is a shallow meadow, about 150 acres, on the west side of the East Branch and can be easily accessed from the main river. According to Ed: “Bink told us that years ago this had been the site of a woods camp where Hemlock logs were stripped before the bark was hauled to tanning factories down river, where the bark’s tannin was crucial to the tanning process”.

The East Branch of the river showing the Bark Meadow landing and the tote road.

Here there was a small shack six or eight foot square with a tin sign on the door PREVENT FOREST FIRES – MFS. This would be their storage building. There was a tote road along the river at this landing leading to the trail to the warden’s camp a short distance South.

This photo is on the meadow side of the tote road at the former location of the storage building. There is no evidence of the storage building today. Note the logging cable that has grown into the tree.

The Monument Line sign on the tote road just south of Bark Camp Meadow

Why the name, Bark Camp Meadow?

Tanning was a very large industry all over the Northeast, wherever there was a plentiful supply of Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis). Between 1840 and 1880, it was one of the leading industries in the State of Maine and by 1880 it was the number two industry in Maine, with hides being sent to Maine from all over the world even from such distant places as China and Australia.

At one time, the largest tannery in the United States was in Winn, Maine and the most northerly was in Bridgewater, Maine. This probably was because of the scarcity of Hemlock north of this area.

Extensive areas of Hemlock were cut, the bark stripped and the logs were left to rot in the woods.

There were huge mounds of bark left in the woods that did not rot. Unlike in the South, where slash left from logging rots in a very short time, our cold climate in the Northeast preserves the bark. There were still piles of bark covered with moss in the woods in the early 1950’s.

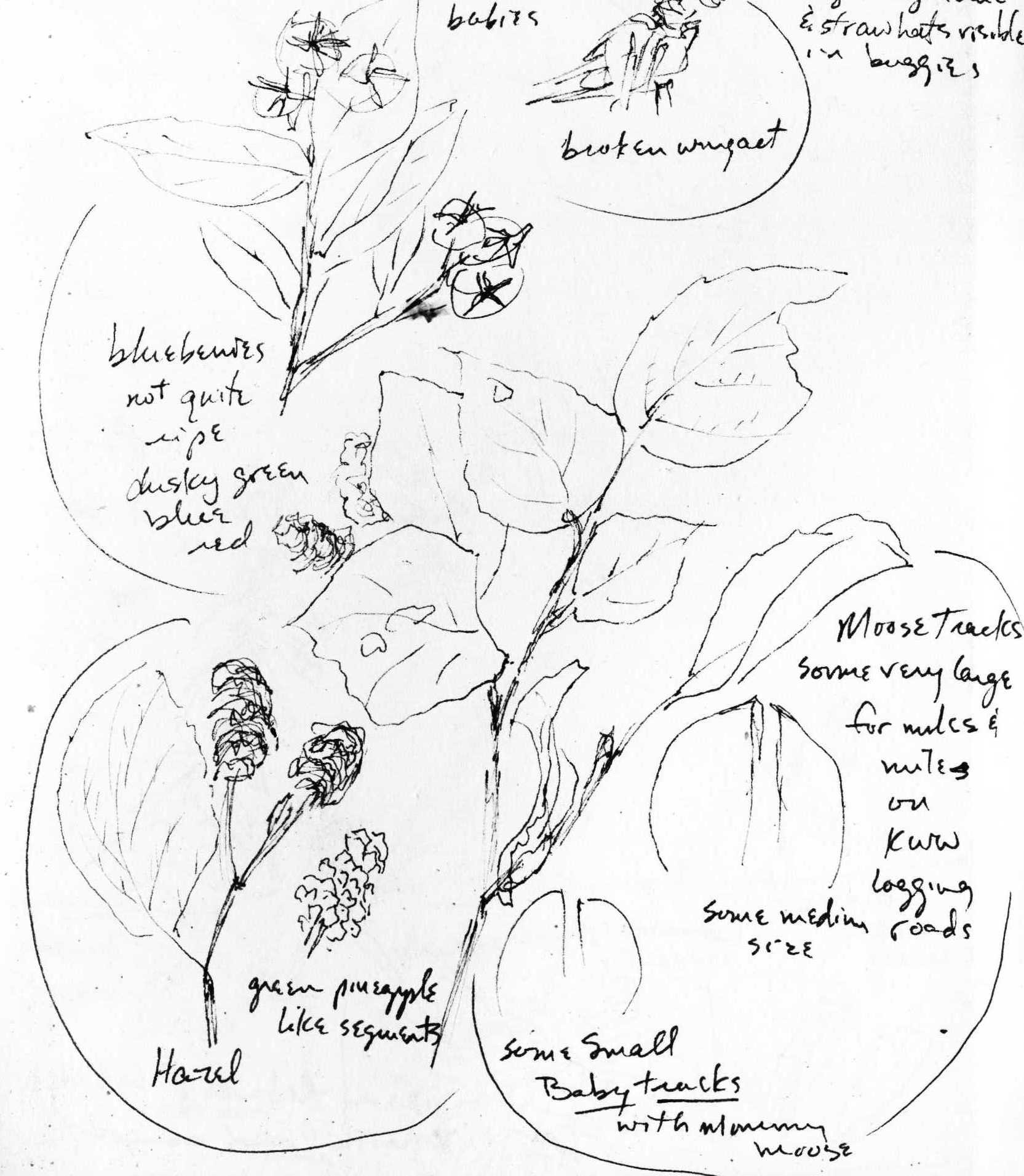

The process of peeling, yarding and hauling the bark to the factories is described in Appendix I of A History of Tanning in the State of Maine by Archibald Riley. This report was for a Masters Degree in Economics, but the Appendix is entirely about woods work and how the men lived in temporary shelters during the peeling season from the full moon in May to the full moon in August. All work was done in warm weather using temporary rough board camps or tents. This operation did not require the permanent buildings needed for logging in the winter in Maine.

The May to August time period is very important, because it is when the trees are growing very rapidly, creating new wood which is soft and slippery under the bark. Later in the season the layer has dried and tightened, making it much more difficult to peel the bark.

The cook was the most important person in the crew. He prepared four meals per day, breakfast and supper at the camp and two lunches in the woods. The cook did all the cooking and baked bread and pies for breakfast for the men. His “cookies” assistants did all the other chores, providing wood and water, cleaning up and delivering the lunches to the men who were working in the woods.**

The crews worked 11 hours a day beginning at five AM and ending at 6 PM with a one hour lunch break in the morning and afternoon.

A crew consisted of four men: a chopper, a knotter, a ring and splitter and a spudder.

With an axe, a ring was cut round the base of the tree and another ring four feet up. Then the bark was split down one side with an axe from ring to ring. A spudder inserted his spud into the split and forced the bark from the tree. A spud is a tool like a very large carpenter’s chisel, curved at the end to fit the shape of the log, with a handle some two to five feet in length. After the bark was forced from the tree, the chopper then felled the tree and the knotter trimmed the branches. The crew then continued ringing and splitting in four foot lengths and the spudder followed. The bark was put up in small piles near the felled tree and collected into larger piles along roads for loading on sleds drawn by teams of horses, for hauling to the tannery. Bark hauling began as soon as there was snow enough to make good sledding. Two cords of bark was about the average load with two horses in fair sledding. A bark hauler, that is, a man and team of two horses, ordinarily received from thirty five to forty dollars a month and board. In 1935, when the Riley report was written, wages for the men averaged about $20 dollars per month and board.

The felling and barking of Hemlock trees was rendered obsolete by the development of chemical processes for tanning hides. The tanning industry, once so prevalent in Maine, has largely disappeared from the state. Bark Camp Meadow still remains!

*wangan is a broad term by used by woodsmen and is taken from the Abenaki. In this case food, household gear, tools and necessities.

**The last project that was done in Maine where the workers lived and worked in the woods for months at a time with a cook and cookie was undertaken by the James W. Sewall Company of Old Town on the Allagash Wilderness Waterway 50 years ago. Felix Cote was the cook and he had worked for the Sewall Company part time for many years. His son in law Joe Sapiel was his cookie. They started with a survey crew at Telos Lake in June. The survey was completed in October at the town of Allagash more than eighty miles from Telos.

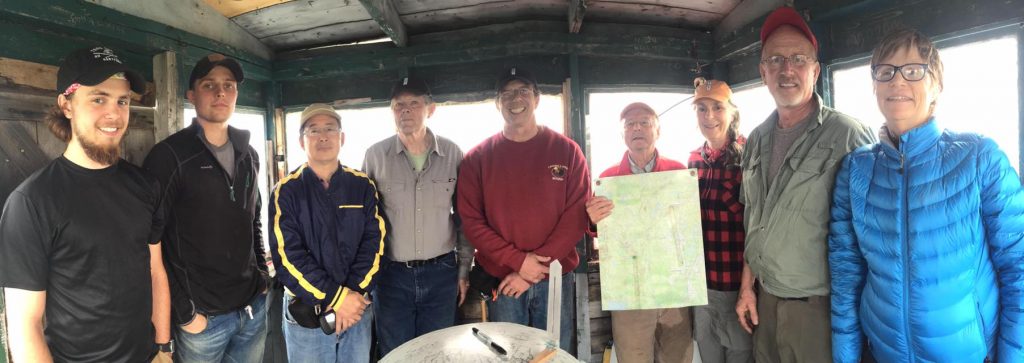

Earl Raymond is a Board Member of The International Appalachian Trail and a VIP for KWWNM.