I first saw the little blue and white plaques while hiking along the East Branch of the Penobscot last fall. IAT-SIA they indicated. Then I became obsessed with them. What were they, where did they go?

An online search showed the trail, from Baxter State Park in Maine clear to the tip of the Gaspe Peninsula in Quebec. I was dumbfounded. And then I read that it continued into the other Maritime Provinces, Greenland, and Europe. My next question was: Who created this trail? I wanted to begin hiking it right away.

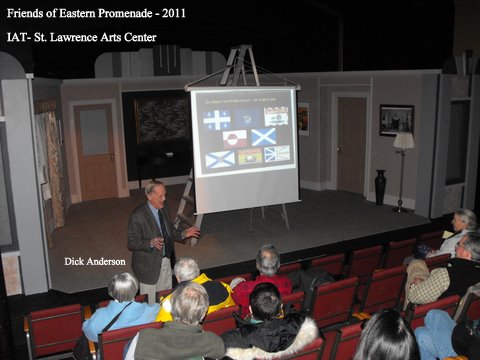

Reaching IAT president and founder Dick Anderson resulted in another half dozen emails coming my way- information from trail volunteers about the sections they maintained. Right away, I sensed a lot of enthusiasm from a diverse bunch of people who seemed delighted that I was interested in their trail.

I’m not a strong hiker, I’m on the upper side of sixty, and I usually hike alone. The first thirty miles is pretty remote, beginning on a large clear-cut parcel following old logging roads, miles away from anything. I planned a four-day trip just to check out that section, hiking backward from my vehicle left in a gravel pit near the East Branch. It was a day’s hike just getting to the trail.

On the first day, I came upon a recently constructed log lean-to on the old tote road near the wild and beautiful Wassataquoik Stream. Pretty good start, I thought, especially since it was raining. Continuing in the rain the next day, I walked the 5.5 miles to the start of the trail at the Park border near Katahdin Lake. The little blue and white markers were all there, well visible on posts at every turn. My confidence in the trail got a solid boost.

This summer, I am walking the IAT. The Maine portion is behind me now, though I veered from the path as I approached Canada since I had a place to rest and revamp for a few days. The little blue and white plaques were my beacons for a couple weeks, those little signs of recognition that said, yep, you’re on the trail. Each one reminded me of the hard work done by a dedicated group of volunteers over the past decade, seeing through their dream of a through-trail along the entire Appalachian spine.

What is a through trail? It’s a trail where a person can begin walking and actually go somewhere. Some people bomb through the trail, their goal a far-away destination. Others, like myself, tend to stroll, though I don’t know anyone else who is as slow as I am.

I took six days to cover the first thirty miles, losing the trail due to inattention in rain and thick mosquitoes, but finding it again after a seven mile detour which was actually quite pretty. The only people I saw in six days were the IAT trail crew, out there cutting and hacking brush in the same rain and bugs I had started out in. Sharing a lean-to with them, I enjoyed homemade fish chowder versus my own dried store. I should add that most of these fellows are pushing seventy, even eighty years old.

The rain cleared for my climb up Deasey Mt. followed by Lunksoos with the reward of another lean-to looking straight onto Katahdin. Lingering at the Grand Pitch lean-to, I spent an afternoon at the brink of the thunderous falls.

The first thirty miles of the IAT passes through a sanctuary where no motorized vehicles are allowed (except for maintenance). It is truly another world full of wildlife, where bear and moose sitings are common. The IAT folks were very pleased to gain permission as well as support to build their trail through this beautiful land parcel skirting two major tributaries of the Penobscot watershed.

Beyond the sanctuary, the trail follows rural roads with a couple shelters along the way. The shelters sit high up on Aroostook County farms. One landowning couple had placed a camper near the shelter for hikers to use in inclement weather, offering coffee, a shower, and a whopping breakfast the next morning.

Soon I was on the multi-use rail-trail which provided three days of flat, easy walking down a shady lane, much appreciated in the sweltering heat of July 4th weekend. I had gotten off the trail hoping to get a hot dog and perhaps an ice-cream cone (treats I would never eat at home), when a picnicking couple offered me a steak fresh off the grill.

As I was about to pitch my tent in a grassy spot near the trail, indicated as an optional campsite, an ATVer suggested I go a little further off the trail to a private campground. The grass was mowed. There were fire pits and picnic tables along a tumbling, clear stream. All I needed was permission from the owner. I was welcome, he said, bringing a stack of wood later for a fire. But I had already joined other campers, friends of the landowner whose hospitality we all shared, to enjoy some miniature fireworks.

On the trail again, I opted out of the climb up Mars Hill where I was promised a spectacular view from the lean-to at the top, sticking with the easy rail trail most of the way to Caribou.

I’m not a purist. A purist will backtrack if he or she misses any part of the trail, to walk every inch of it. It’s part of the integrity in saying, “I hiked the IAT”. I call myself a convenience hiker. If the trail is convenient and fun, I’ll hike it. If not, I’ll find my own way. The offer of a rest for a few days is reason for a detour. But I missed the little blue markers which seemed to say hello from the founders of this trail and the volunteers who have worked so hard to mark and maintain it, like a bit of encouragement along the way.

Tomorrow, I’ll be on the trail again, following my own route along the pretty Aroostook River to Fort Fairfield and the border. From there I’ve had to make a decision. Continue as a through-hiker across the northeastern part of New Brunswick and on to the rugged Chic-Chocs of the Gaspe Peninsula, or take a bus. I’m hopping the bus- straight to Prince Edward Island followed by Nova Scotia, to hike the IAT in those beautiful provinces. I’m a segment hiker, mixing up the segments, no less, to suit my own whims.

Already, half a dozen people from the two provinces have emailed me with a welcome, telephone numbers, and information about their portions of the International Trail. Some provinces provide online step-by-step instructions with maps as the Maine chapter does; others refer a hiker to government-funded guidebooks available for purchase. Some have free shelters as Maine does, others require a pass fee for shelter use, and others provide tourist information of places to stay. Every province has something different to offer from sheer wilderness and rugged mountains to seaside marshland and pretty little farms and villages brimming with culture. I’ve opted for the latter in the summer’s time remaining.

Like the trail folks, I have a dream also. If all goes well this summer, I hope to hike the ancient ways of Ireland next year where I might well see the familiar blue and white plaques if the IAT plans go forward. And from there, who knows. Did they say Spain and Morocco