“Let’s follow the moose” – those were literally the words my father, Frank Wihbey, uttered at one point as we sought to mark out the course of the early International Appalachian Trail. And follow the moose we did.

In a long life of hiking, it was to become one of my father’s favorite anecdotes. He loved the story’s sheer absurdity. It appealed to his quirky sense of humor. But it also illustrated for him that following nature was often the solution.

This was in the “pioneer days” of the IAT, an effort my father joined in its beginning stages.

As I recall, Dick Anderson had tasked us with setting out signs right on the Canadian-American border, and after a few hours of walking and blazing, a patch of marshy ground materialized before us. Which way to go? We sat and gnawed on granola bars and discussed the apparently limited possibilities. After a time, though, a cow moose appeared. We watched with amusement as she meandered in front of us, then steered around the wet ground and found a gap in the bushes.

The solution was upon us. Dad dove into the brush behind her, and we had our bend in the trail. It was a rare moment of pure trail whimsy for him, and he relished it.

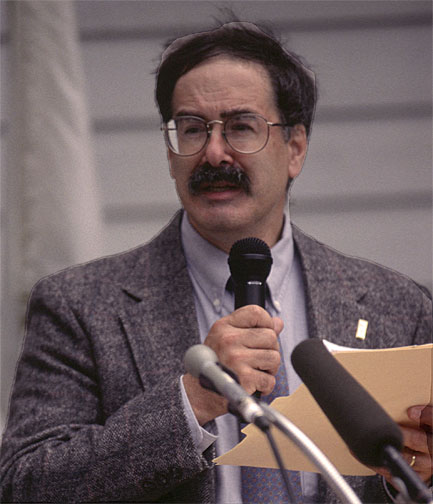

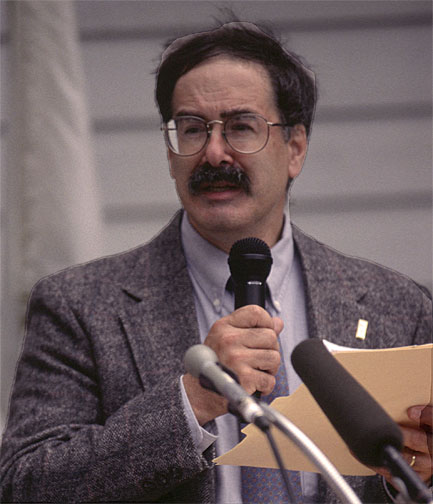

The moose tale aside, my father was the most deliberate, careful, and well-prepared outdoorsman I ever knew. Perhaps the supremely puzzling fact of his life story now is that he died in an unfortunate accident. For those who are not already aware of the news, he slipped and fell while hiking alone on the coastal bluffs around Torrey Pines State Reserve in San Diego, California. That was January 12, 2010. He had been visiting his daughter (my sister), Lynn, who lived in the area. He was 65, just a few months into retirement after a long career as a librarian at the University of Maine.

My father served on the IAT board for a time, and though he gave up that slot a few years ago, the lessons and stories he took away nourished him through his last days. It was, without a doubt, one of the proudest associations he had in life.

I was speaking with my mother, Karen Wihbey, the other day, and she was recalling the pure admiration he always had for Dick Anderson: his intrepid spirit; how he was always encouraging people to do more, to transcend themselves. My father would at times say to me something along the lines of, “Dick wants me to do this. I can’t possibly do it. But Dick makes anything possible!”

I recently emailed with Dick. He wrote to me, “Your father was such a nice man and I will miss him. It is really too bad that he didn’t get to enjoy more of his retirement, but fate calls us in a random manner and some of us have just been lucky.”

Though my father was unlucky in one sense, he was nevertheless lucky in another. He got to know the many amazing souls who have helped build the IAT. Of course, there are so many other names to mention here. I only wish my father could be here to do them all justice. He was forever marveling at, and telling stories about, the people who loved the trail, like M.J. Eberhart, "Nimblewill Nomad.”

When Will Richard found out recently that my father had died, he said he was in disbelief. But he also wrote the following: “Your father represented so much of life with his wit, it is really difficult to comprehend his passing. Frank was always for us – in every way – for the IAT.”

Our family takes great joy in such expressions of praise. It has been a painful way, obviously, to start this new year. But we have been remembering all his accomplishments, including the fact that, in addition to hiking good chunks of the IAT north of Katahdin, he had completed the Appalachian Trail’s southward stretch from Maine to New Jersey.

Frank Wihbey loved languages, and he knew the basics of perhaps ten different tongues – from ancient Aramaic to Spanish. One of the great attractions of the work of IAT – or Sentiers International Des Appalaches – was that he got to use his French language skills. One of the wonderful fruits of his collaboration with Jocelyne DeChamplain, of Matane, Quebec, was the bilingual hiker’s guide they produced. Dick Anderson tells me that it is still in print.

Now, I tell this last part of his story because I know hikers need to know the details.

The outdoors are always unpredictable, and it’s in the hiker DNA to seek specifics, and to learn. Indeed, my father’s final lines in his journal relate to how he had put too much in his backpack on a previous day’s hike in California, and how he was determined to have a lighter load. The last words he wrote in that journal – in addition to recording the various bird species he observed – were “live and learn.”

The cliffs at Torrey Pines State Reserve are some 300 feet high, with many danger signs posted around them. My father appears to have slipped on the sandy soil. The terrain is quite different than the roots-and-rocks he was used to in the East. The authorities said the evidence shows he was trying to hang on. They found him about 100 to 150 feet down the side of the bluffs. He was located after the search and rescue folks pinged the GPS chip in his IPhone, and lowered down a man from a helicopter. My father had died in the fall.

Of course, this is a difficult reality to grapple with, or to put again in words. But I know my Dad above all sought clarity and truth.

I don’t take his final words, “live and learn,” as something ominous or ironic. I take them as prescient encouragement to all of us – to those who are living – to keep going, to keep learning, to keep loving what we are doing.

Frank Wihbey loved the outdoors and loved the trail. We all imagine that somewhere, on some overgrown, bush-ridden path way out in the wilderness, he is still in some sense sauntering along, following the moose into nature.